Last Updated: January 21 2025

This is a guide on how to give conference talks. As someone who loves public speaking and loves giving conference talks, I was surprised by how many people loathe and/or fear public speaking (75% of people fear public speaking as their number one fear [1]). Thus, I created this guide in the hopes of easing people’s fears and improving the state of conference talks!

I split this into four areas. First, I give broad principles and advice. Then some advice on improving the content of your presentations (both what you say as well as what is on your slides), followed by tips on delivery. And finally I conclude with Q&A.

A few caveats:

My first tip is unfortunately going to be rather mundane. I wish I could tell you something along the lines of:

Sleep every day at 11:00 PM to the sound of Mongolian throat signing. Wake up at exactly 3:47 AM and eat three cucumbers topped with Nutella. Immediately fall back asleep, but wake up 20 minutes later for a 3 hour run. Do this and in 57 days you will become a public speaking GOD.

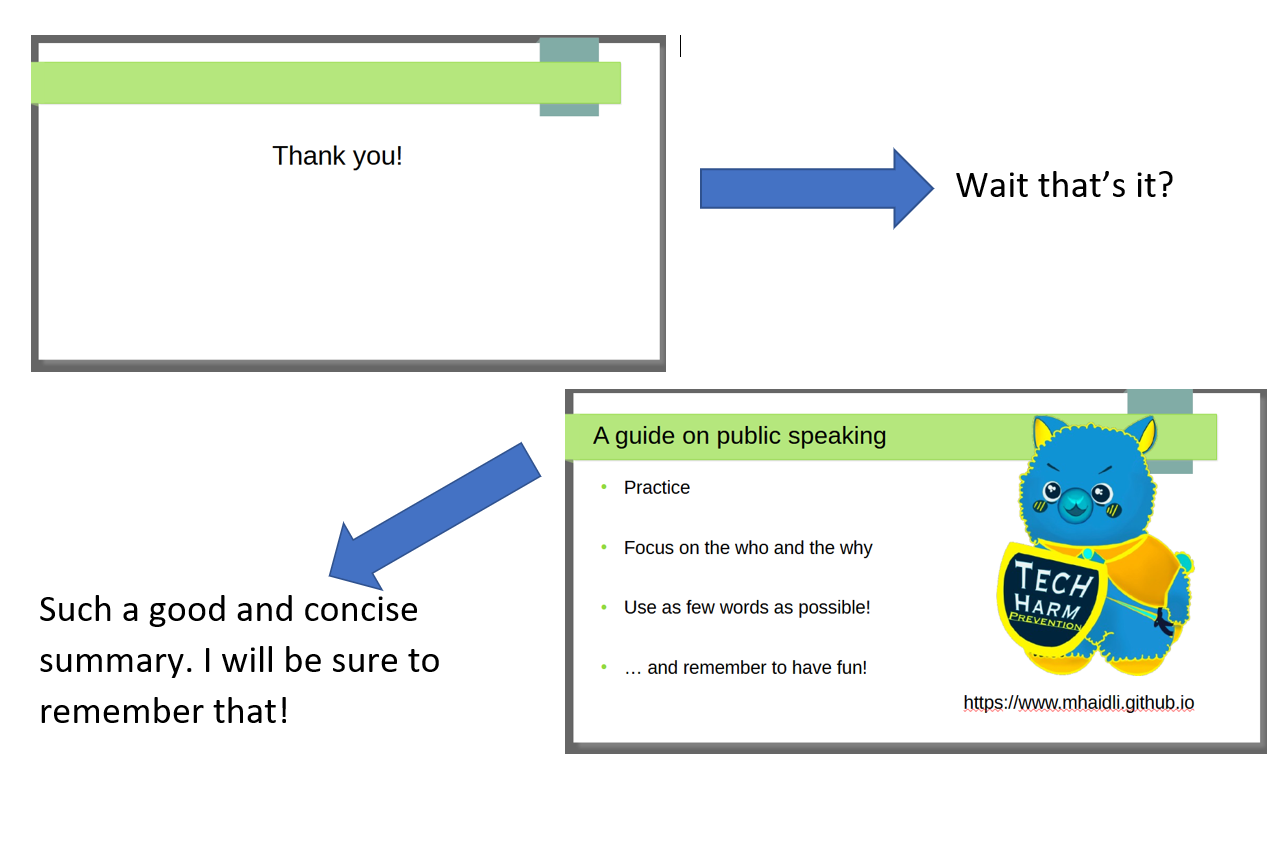

Instead, my advice is much more mundane, and that is to practice. The more you practice, the better you are. By practice I mean both practicing giving talks in general and practicing each individual talk. I practice each conference talk I have to give at least three times, and ideally at least twice with a finalized version. The goal is not only to improve my delivery and the content, but to become so familiar with the content of a presentation that I can almost recite it by heart. That way, when speaking, I am not scared of freezing up because even if I somehow freeze up, given that I have memorized the speech and practiced it so much, I can easily ground myself, figure out where I was, and continue from there.

When practicing, I like to practice in front of an audience. Not only does this better simulate the real conference talk, but I also have a group of people who can point out flaws in my presentation. In fact, in my previous lab (SPILab), it was customary to create a shared document (e.g., a GoogleDoc) where people would write feedback, and that way you got live reactions to your content.

My second piece of advice is to focus on the who and the why of the talk. Too often, when we are tasked with giving a talk, we dive immediately into what we are going to say, what parts of a study we are going to highlight, and what presentation-creating software we are going to use without really reflecting on who we’re talking to and why we are talking to them. The who and the why, though, is an important factor to take into account because knowing the who and the why will greatly affect what we should be delivering and the effectiveness with which certain messages can (or cannot) be conveyed. Take the following three scenarios:

Each of these scenarios involve three different audiences with three different purposes. All three talks may be about the same study, but because they are tailored for different audiences and different purposes, then you might change how you present it. For example, at an academic conference, maybe you want other people to know of your work and cite it, so you focus more on the findings and conclusions. For a job talk, you may want to highlight a unique method that you developed to show how smart you are, so maybe you focus more on the methods part. When you’re talking to high schoolers, maybe you want to motivate the problem and talk about that a lot more, as well as using simpler language. Understanding the who and the why will enable you to tailor both the content of your presentation as well as the style, in order to make it more effective, get across the message that you want to get across, and thus fulfill your goals.

My final piece of broad advice is to focus more on what you are going to say rather than the slides. I know it is extremely tempting to work on slides. Someone tells you to talk about something, and you immediately open PowerPoint and add a bazillion cute images and fancy word fonts, and you spend hours agonizing over what theme to use. I understand the motivation. Slides are visual; words are not. You can alter the words you say on the fly, whereas there’s something definitive and final about slides. However, I will be the first to say that what you say is much more important than what is on the slides. I would much rather go to a talk with an engaging speaker and the most boring slides in the universe than someone with amazing slides who is barely audible. Remember, public speaking predates PowerPoint: in fact, there is a whole genre of public speaking (i.e., speeches) that do not rely on PowerPoint or visual cues at all, and are still engaging and interesting.

Thus, I advise you to prioritize and spend more energy on what you are going to say rather than the slides. For me, I take the “words > slides” to an extreme in that the first thing I do is to write out verbatim what I’m going to say, and only then do I focus on creating slides and structuring them around my content.

Since we live in an AI hellscape, I asked ChatGPT what a signpost is, and it answered the following:

“In a literal sense, a signpost is a physical sign or marker, often used on roads, trails, or in public spaces, to provide directions, distances, or information. For example:

In public speaking, though, a signpost is you letting the listeners know where you are in the presentation, what you will be talking about next, and how much time is left in the presentation. This is invaluable for presentations that are long (i.e., longer than 20 minutes.) It helps people reset and prevents people from wondering “Oh dear Lord how long is this person going to keep yapping on for?”

There are many ways you can signpost during an academic talk. You can put an outline at the beginning and constantly refer back to it. You can put a progress bar at the bar. You can put section headers. The options are endless, but the crucial thing is letting people know where they are at, where they are going, and how much time is left.

The next piece of advice is one you’ve probably heard of before, but it bears repeating: have as few words on your slides as possible. One key thing people forget is that slides are not your speaker notes. Your slides should contain the bare minimum number of words so that people can roughly follow your point, and you expand on those words with your oral presentation. In fact, if possible, try not to use any words at all. They say a picture is worth 1000 words, and if using images means you can get rid of words, then the better.

The final piece of advice I will give is to not have a final thank you slide. There’s nothing wrong with a thank you slide, but it is a huge wasted opportunity. The final slide is the slide people will leave away with, the one they will be staring at during the Q&A, and the one that they will remember to take a picture of. Don’t just have a thank you. Put in the following:

And you can even include a thank you message in the slide. But don’t just add a Thank You. Add the other information as well!

Along the lines of words being more important than what you say, another underrated part is delivery. How you say words matters just as much as what you are saying. What is the point of the best research presentation ever if no one can hear it? Thus, here is some tips focusing on the delivery.

First, before starting to speak, always do a mic check. I tend to ask, “Can folks in the back hear me?” and wait for approval before continuing. This avoids the embarrassing moment where, five minutes into the presentation, someone finally raises their hand to tell you they haven’t been hearing you the entire time and asked you to please restart. Moreover, it helps you adjust your speaking volume.

When we are up on stage, something interesting tends to happen. We feel that we need to talk, and so, if we are not talking, we are failing at our jobs. Thus, we fill out every possible second with talking, talking, more talking, even when it doesn’t make sense and we’re not saying anything meaningful, and we’re just using fillers.

This is where I have to tell you: pauses are okay. No one expects you to be Eminem and spit 10,000 words a minute. In fact, pauses are not just OK; you can use them for dramatic effect! You can use them to emphasize a point, build up anticipation for a concluding sentence, and so much more. Aesthetically, a pause is so much better than an “um” or an “eh” or an “uhh”… Embrace the pauses. They let you think about where to go next and let you reset, as well as letting the audience ponder about what you’re saying. It also makes you seem wise! Now, this does not mean you get to take 30 second pauses between words. But the occasional brief pause is not only ok, but it can elevate your presentation skills to the next level.

When delivering the speech, make sure not to just look down at your notes. Not only does this look strange, it also means that your voice is projected to your laptop / notes document (instead of the audience). Look up at the audience often, and make sure to change who you are staring to every time. This is where practice comes in handy: if you have practiced your speech enough so that you have basically memorized the entire thing, you won’t need to look at your notes as much. But even in cases where you have not memorized it perfectly, you can still look up and deliver. You should first look at your notes, memorize the sentence while saying the first few words, and then look up and complete the sentence. This is where pauses are important. Deliver a point, use a pause for emphasis, and while the audience is busy taking in the magnitude of whatever insight you have shared, you quickly scan ahead and memorize the next nugget of wisdom to share with the crowd.

Next up, try to avoid being monotone. Feel free to change your tone of voice and the speed as you talk. Start quiet, speed up and get louder, pause for dramatic flair, deliver a jaw-dropping truth bomb. Speaking in monotone puts people to sleep. Remember, you are talking to your audience, not reading to them.

When I look online at advice for giving presentations, something I often find is a lot of people saying “Oh, you should interact with the audience. You should ask questions of the audience. You should engage in audience participation”. I understand the temptation: when done well, audience interaction works really well. Everyone remembers that presentation where the author bantered with the audience and got the audience hooked into whatever they were saying. However, my advice runs a bit counter than that. Sure, if audience interaction works out, it can be amazing. A failed audience interaction, however, is one of the most horrible, cringe-worthy, embarassing thing ever. Nothing is more awkward than a presenter asking a question of an audience who is tired, does not want to be there, and would much rather be at the beach. No one answers, the presenter does not know what to do, everyone feels bad for the presenter, and it’s just a rough time for everyone. Thus, my advice is the opposite: stay away from audience interaction, or more accurately, don’t force it. Sure, if you’re feeling it, if you are motivated, if you feel the audience has energy, then engage with it. It can definitely elevate your presentation. But don’t force it. If it’s not natural to you, if the moment doesn’t feel right, it’s much better to have no audience interactions. Plenty of speeches or public speaking presentations don’t have audience interactions and are still great, memorable and get their point across. Be cautious when engaging with the audience, and don’t wedge it in there when it doesn’t belong.

Handling Q&A could be a whole blog post in itself. It can be the most nerve-wracking part of any presentation because, unlike the speech (which you can prepare for), the Q&A doesn’t depend on you, and you don’t know what curveballs the audience may throw at you. Plus, there is the fear of the nefarious ******* who just gets up and says, “You are stupid”, and sits down. So, what tips can we use to handle the Q&A?

My first piece of advice is that while you cannot fully predict Q&A, you can still practice it. You can still anticipate roughly what types of questions people may ask, and this is possible if you practice in front of an audience. If you are presenting at an academic conference, invite some of your colleagues from your department to sit in and listen to your talk, and ask them to pretend they are at the conference and ask real questions. The questions that they have will likely be similar to the questions that the real audience will have.

OK, what if it’s a question you haven’t anticipated? The first thing is you don’t feel obligated to dive straight into answering. Remember, pauses are cool. You can take a breath and think about it. And if you need some time to think about it, one useful trick that I use is to reformulate the question. For example:

Audience Member: Thank you for the presentation! I wonder if you could speak a little bit more about why you think there are discrepancies between people with CS degrees and those without CS degrees in their answers to the survey.

Me, wanting to buy time: Hmm let me rephrase your question to make sure I am getting it right. So you are asking what I think causes the difference in the scores between people who have not studied CS and those who have?

Audience member: Yes.

Me, having used those extra 8 seconds to think of the perfect answer: [THE MOST AMAZING ANSWER IN THE PLANET]

You can also buy time for thanking people for their questions (but don’t do this on every question; otherwise, it looks obvious that you are not really thanking them and are just buying time.)

What if you get a question you either can’t answer (because it is too difficult) or one that you shouldn’t answer (because it is bad faith and mean spirited)? Here is the golden rule:

“Thank you for that question. Unfortunately, I cannot answer that right now, but I would be happy to follow up offline”.

And move on to the next person. If they keep insisting? Be gentle but firm:

“Thank you, but in the interest of time, I must insist on moving along. Do not worry, I will address your question offline”.

And if they keep pestering you? Well, (A) this never happens and (B) if it does, let them ramble. Everyone in the audience can see that they are the ones being unreasonable (not you), so stand tall and firm as they drive their own reputation into the ground, using their pauses to repeat the statement above.

I hoped I would have something witty to end this guide with, but alas, I do not. I expect to update this as I get better at giving public presentations, but until then, I hope this was useful!